10. The Destruction of Aleppo: The Impact of the Syrian War on a World Heritage City

- Francesco Bandarin

دمار حلب: أثر الحرب السورية على إحدى مدن التراث العالمي

فرانشيسكو باندارين

تعرّضت حلب لدمار هائل خلال الحرب السورية بين عامي 2012-2016 عندما كانت المدينة مركز اشتباكات ضخمة بين قوات الحكومة السورية والمعارضة. يقدّم هذا الفصل سردًا لتطور الحملة العسكرية ويُقيّم كلًا من الدمار الذي خلّفه النزاع، والقيود التي يعاني منها النظام العالمي لحماية التراث.

ملخص

تعرّضت المدن والمواقع السورية لدمار هائل خلال الحرب التي امتدت عشر سنوات بين عامي 2011 و2020. والوضع الأسوأ هو في حلب، هذه المدينة التي تعرّضت للدمار خلال النزاع بين عامي 2012 و2016. تأثر السكان بذلك على نظام واسع، حيث غادر مليونا شخص المدينة، وسقط أكثر من خمسة وعشرون ألف قتيل. وقد تعرّضت كافة مناطق المدينة لضرر جسيم وأهم ما فيها من صروح وأسواق وخانات ومساجد. كما تعرّضت الوحدات السكنية لضرر بالغ، بينما حُرم السكان من الماء والكهرباء والخدمات الصحية والتعليمية. يستعرض هذا الفصل تطوّر النزاع، وتأثيره على البنى الاجتماعية والمادية للمدينة، ودمار تراثها الثقافي المهم، والدور الذي اضطلعت به الأطراف الوطنية والدولية خلال الحرب. وأخيرًا، يُقدّم الفصل تقييمًا للوضع الحالي، والقيود التي يعاني منها النظام العالمي لحماية التراث خلال النزاعات.

阿勒波的毁灭:叙利亚战争对世界遗产城市的影响

弗朗切斯科·班德林 (Francesco Bandarin)

阿勒波在 2012-2016 年叙利亚战争期间遭受了大规模破坏,当时这座城市是叙利亚政府军与反对派之间主要冲突的中心。本章记述了军事活动的演变,并分析了冲突造成的毁灭性打击以及国际遗产保护体系存在的局限。

摘要

叙利亚的各大城市与遗址在 2011-2020 年的十年战争期间惨遭毁灭性袭击。阿勒波的状况最为惨烈,在 2012-2016 年的冲突中几乎被完全摧毁。那里人口锐减至仅剩两百万人,伤亡人数超过 25,000 人。该城所有地区及其主要纪念碑、露天市场和清真寺均受到严重的损毁。房屋同样受到较大程度的破坏,而市民丧失了水电、健康与教育服务。本章探究了冲突的发展过程、其对城市社会与建筑结构的影响、对重要文化遗产的摧毁以及叙利亚国内外行动者们在战争中起到的作用。最后,文章分析了国际遗产冲突保护体系的当前状况与存在的缺陷。

Aleppo suffered massive destruction between 2012 and 2016 during the Syrian war, when the city was at the center of major clashes between Syrian government forces and the opposition. The chapter provides an account of the evolution of the military campaign and assesses both the devastation produced by the conflict and the limitations of the international system of heritage protection.

Abstract

Syrian cities and sites suffered devastating destruction during the ten-years’ war of 2011–20. The worst situation was found in Aleppo, a city all but destroyed during the conflict between 2012 and 2016. The population has been heavily affected, with two million leaving and over twenty-five thousand casualties. All areas of the city and its major monuments, souks, khans, and mosques suffered severe damage. The housing stock was also badly damaged, while the population was deprived of water, power, health, and educational services. This chapter examines the development of the conflict, its impact on the social and physical structures of the city, the destruction of the city’s important cultural heritage, and the role played by national and international actors during the war. Finally, it assesses the current situation and the limitations of the international system of heritage protection during conflict.

La destruction d’Alep : l’impact de la guerre de Syrie sur une ville inscrite sur la liste du Patrimoine mondial

Francesco Bandarin

Alep a subi une destruction massive au cours de la guerre en Syrie entre 2012 et 2016, lorsque la ville se trouvait au centre d’affrontements majeurs entre les forces du gouvernement syrien et l’opposition. Le chapitre fournit un récit de l’évolution de la campagne militaire et une évaluation tant de la dévastation causée par le conflit que des limitations du système international de protection du patrimoine.

Résumé

Les villes et sites syriens ont subi une destruction considérable durant la guerre de dix ans entre 2011 et 2020. La situation la plus déplorable se trouve à Alep, une ville quasiment détruite par le conflit entre 2012 et 2016. La population a été lourdement affectée, avec le départ de deux millions de personnes et plus de vingt-cinq mille victimes. Tous les quartiers de la ville et ses principaux monuments, les souks, les khans et les mosquées, ont subi des dégâts considérables. Le parc immobilier a également été gravement endommagé, et la population a été privée d’eau, d’électricité, et de services médicaux et éducatifs. Ce chapitre examine le développement du conflit, son impact sur les structures sociales et physiques de la ville, la destruction de son important patrimoine culturel, ainsi que le rôle endossé par les acteurs nationaux et internationaux durant la guerre. Enfin, il propose une évaluation de la situation actuelle et des limitations du système international de protection du patrimoine durant le conflit.

Разрушение Алеппо. Последствия войны в Сирии для города - объекта Всемирного наследия

Франческо Бандарин

Во время сирийской войны 2012-2016 годов Алеппо оказался в центре ожесточенных столкновений между правительственными войсками Сирии и оппозицией, вследствие чего подвергся массовому разрушению. В этой главе описывается последовательность событий военной кампании и оценивается как ущерб, нанесенный конфликтом, так и недостатки международной системы защиты культурного наследия.

Краткое содержание

За те десять лет, что шли военные действия, с 2011 по 2020 год, сирийские города и культурные объекты подверглись массовому разрушению. Наиболее трагична история Алеппо. В результате конфликта между 2012 и 2016 годами город оказался в руинах. Значительно пострадало население. Два миллиона человек покинули город, двадцать пять тысяч убиты или ранены. Все районы города, важнейшие памятники, базары, караван-сараи и мечети были серьезно повреждены. Разрушению подвергся и жилищный фонд, население осталось без воды, электричества, больниц и школ. Глава описывает развитие конфликта, его влияние на социальную и физическую структуру города, разрушение важнейших культурных памятников, а также роль национальных и международных сил во время войны. Наконец, автор оценивает текущую ситуацию и ограничения международной системы защиты культурного наследия во время конфликтов.

La destrucción de Alepo: el impacto de la guerra siria en una Ciudad Patrimonio Mundial

Francesco Bandarin

Alepo sufrió una destrucción masiva durante la guerra siria de 2012 a 2016, cuando la ciudad se convirtió en el centro de importantes enfrentamientos entre fuerzas del gobierno sirio y la oposición. Este capítulo proporciona un recuento de la evolución de la campaña militar y evalúa tanto la devastación producida por el conflicto como las limitaciones del sistema internacional de protección del patrimonio.

Resumen

Las ciudades y los sitios sirios han sufrido una destrucción devastadora durante los diez años de guerra entre 2011 y 2020. La peor situación se encuentra en Alepo, una ciudad que quedó prácticamente destruida durante el conflicto entre 2012 y 2016. La población se ha visto fuertemente afectada: dos millones han abandonado la ciudad y ha habido más de veinticinco mil víctimas. Todas las zonas de la ciudad y sus monumentos más importantes, zocos, caravasares y mezquitas han sufrido graves daños. El patrimonio inmobiliario también se vio gravemente dañado, mientras que la población quedó privada de agua, electricidad, servicios sanitarios y educativos. Este capítulo analiza el desarrollo del conflicto, su impacto sobre las estructuras sociales y físicas de la ciudad, la destrucción de sus importantes sitios de patrimonio cultural y el papel desempeñado por los actores nacionales e internacionales durante la guerra. Finalmente, evalúa la situación actual y las limitaciones del sistema internacional de protección del patrimonio durante el conflicto.

Ten years of war have destroyed Syria’s economic, social, and cultural structures. The country that existed in 2011 is hardly recognizable today, except for a few areas that have been preserved from destruction.1 This chapter addresses the destruction of the World Heritage Site of Aleppo during the conflict that raged in the city from 2012 to 2016. In addition to an assessment of the physical destruction of the city’s cultural heritage, housing, and infrastructure, also examined are the impact of the war on the social fabric of the city and the role played by the different national and international actors involved in the conflict. Finally, the effectiveness of international law for the protection of cultural heritage and of civilians during the Syrian war is discussed.

In 2011, Syria was already in poor economic condition, following a long global recession and a chronic inability to develop a modern industrial sector. Over half the national product came from the primary sectors—agriculture and mining—with industry representing just 3–4 percent of the total.

Within a few months of the start of the conflict, the country’s economic situation declined precipitously: oil resources largely fell into the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS, also known as ISIL or Da’esh) and the Kurdish forces, deepening a recession caused by sanctions and devastation. Meanwhile, consumer prices also rose sharply,2 while the national currency, the Syrian pound, depreciated significantly, and black markets arose for essential products, further stretching people’s ability to purchase necessary goods.3 Most basic public social services, from health to education and social assistance, collapsed, with half of all children out of school for most of the decade. Diseases such as typhoid, tuberculosis, hepatitis A, and cholera again became endemic, as did polio, which had previously been eradicated in Syria. The conflict has not spared the health infrastructure of the country, as half of all hospitals have suffered significant damage, especially in urban areas fought over, including Aleppo, Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor, and Idlib.

Private activities, ranging from services to commerce, arts and crafts, and transport have also suffered losses and disruption. The devastation suffered by Syria’s physical infrastructure, including residential and commercial buildings and industrial complexes, has caused a huge loss of income and pushed millions into poverty. The UN Development Programme (UNDP) underlines the problem: by 2016 Syria had fallen to 173rd place on UNDP’s Human Development Index, out of 188 countries.4

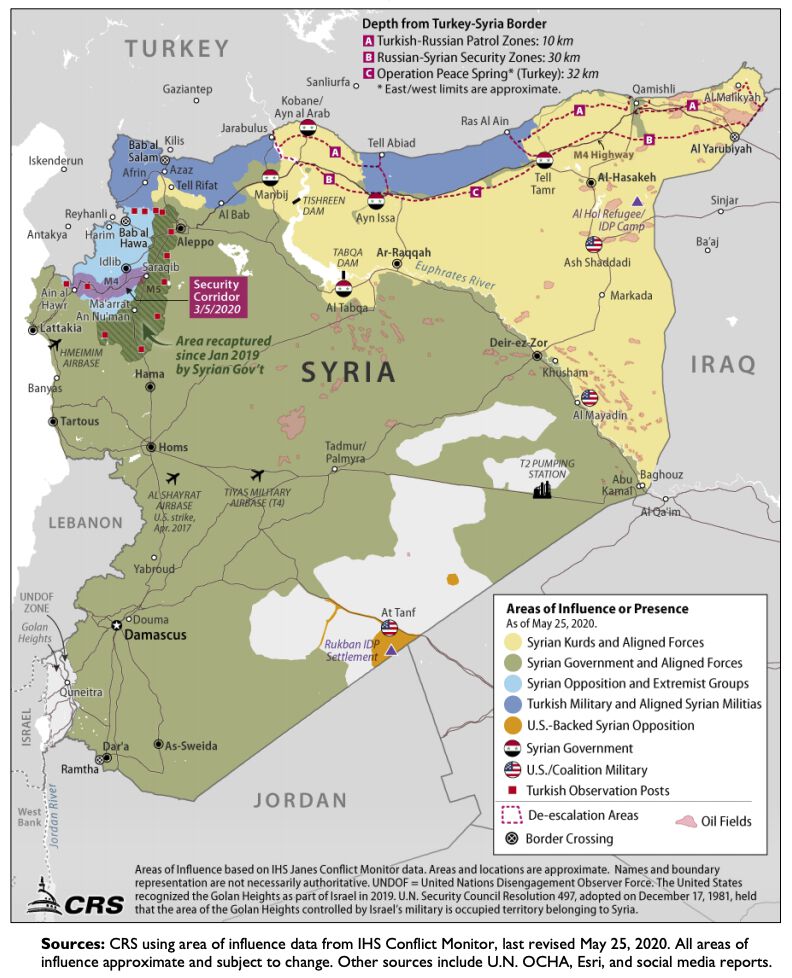

But the worst calamity has been the dispersal of the Syrian population due to the violence. In 2010 Syria had an estimated population of 21.8 million, which shrank to 20.5 million in 20155 and 19.4 million in 2018. It is estimated that at least five hundred thousand people were killed and two million wounded during the war; over 6.5 million people were internally displaced, and over five million, equal to over 20 percent of the country’s population, became international refugees. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the refugees are, still today, dispersed throughout neighboring countries and Europe: almost 40 percent are in Turkey, 35 percent in Lebanon, and 14 percent in Jordan, with the rest in Egypt, Iraq, and Europe (mostly Germany).6 And as of mid-2020 this long conflict was not yet over, although fighting was limited to specific pockets of resistance, such as in Idlib Province in the northwest (fig. 10.1).

Figure 10.1

Figure 10.1Damage inflicted on the physical infrastructure of Syria, including its monuments and historical and heritage places, has been immense, due to the direct impact of war and the loss of control by the authorities over the country’s vast archeological and cultural heritage. Direct damage was caused to many historical monuments and sites when they were used by armies and militias for shelter or as military outposts to control the surrounding areas.7 This is the case, for example, for the citadels of Homs, Hama, and Aleppo, the medieval Crusader castle of Crac des Chevaliers/Qalʿat al-Ḥusn, and the Qalʿat ibn Maʿan fortress in Palmyra. While some monuments were damaged accidentally, such as the al-Wakfya Library in the Great Umayyad Mosque of Aleppo, many were deliberately destroyed, such as the important temples of Bel and Baalshamin in Palmyra, dynamited by ISIS in 2013.8

Entire urban areas, many of them of great historical value, have been devastated: besides Aleppo (fig. 10.2), the old cities of Homs, Daraa, and Bosra have suffered heavy damage.9 The conflict environment also enabled looting on an unprecedented scale. All the major archaeological sites of Syria have been subject to massive illegal excavations aimed at retrieving archaeological “treasures” to sell on the black market, including the ancient Sumerian city of Mari (Tell al-Harīrī), the site of Ebla (Tell Mardikh), the Hellenistic and Roman sites of Apamea (Qalʿat al-Madhīq), and Dura-Europos, resulting in a great loss of historical and archaeological value.10 Damage to natural heritage was also significant, with many forests and oases bombed and burned.

Figure 10.2

Figure 10.2The War in Aleppo: A Social and Cultural Tragedy

The so-called Battle of Aleppo, one of the longest and most deadly conflicts since World War II, raged for five years, from 2012 to the end of 2016, and involved a range of actors, both on the Syrian government’s side (the Syrian army, Hezbollah, other Shiite militias, Iranian government forces, and later the Russian army) and on that of the opposition (the Free Syrian Army, the Aleppo Military Council, ISIS, the Levant Front—also known as al-Jabha al-Shamiya—Jabhat al-Nusra, and the Syrian Islamic Front). Kurdish militias such as the People’s Protection Units (YPG), other US-backed groups, and the Turkish army were also involved. Many of these groups were loosely organized, with frequent movements of fighters from one to another.

The war in Aleppo took place over several phases, with different degrees of destruction and impact on a civilian population that paid a very high price, affected directly by aerial bombing, shelling, snipers, mine explosions, fighting, and indirectly by food deprivation, destruction of health facilities, lack of water and electricity, and transfers to refugee camps. Humanitarian organizations involved in the conflict, observers, and scholars11 have attempted to collect information from the conflict areas, enabling an understanding of the conflict’s evolution and its impact on the population, on the city’s infrastructure, and on the city’s heritage.12 The war can be schematically divided into four phases, each of which is discussed in turn: the opposition takeover of Aleppo (2012–13), the reaction (Operation Northern Storm, 2013–14), the war of attrition (2015), and the retaking of the city (2016).

Although military operations started at the beginning of 2012 when the Free Syrian Army took control of areas in the north of the city, fighting began in July of that year, when the nearby town of Anadan was captured, opening the way to the capture of the city. The reaction of government forces was immediate and strong, involving the use of tanks, snipers, and aerial bombing, destroying many buildings and public facilities. In September, from the north and east, fighting reached the Old City of Aleppo, and shelling extensively damaged the central market area of al-Madina Souk, with the loss of about a thousand shops. In October, the Great Umayyad Mosque suffered its first wave of destruction when opposition forces attacked it to expel government soldiers.13 By the end of 2012, government forces had lost important positions, such as Sheikh Suleiman army base to the west and the infantry school north of Aleppo, and were increasingly isolated in the city’s western areas. In February 2013, ISIS captured the air defense facility near Aleppo International Airport, and aerial bombing in the city intensified, especially on its eastern side. The violence led to the first exodus of the city’s civilian population, with over three hundred thousand people fleeing to Turkey and other parts of Syria. Heavy fighting took place in the Old City, as the citadel was under the control of the Syrian army.14 On 24 April 2013, the medieval minaret of the Great Umayyad Mosque was destroyed.

After having lost most of their strongholds in the Aleppo countryside by mid-2013, government forces were effectively encircled within the city, provoking a counteroffensive, Operation Northern Storm. This was launched in September, and the army, supported by allied militias, managed to retake the air defense facility from ISIS. Shelling and bombing intensified, with great impact on the civilian population. Late that year, infighting started between ISIS and other opposition forces, enabling the government to regain control of some areas of the city, including the strategic Sheikh Najjar industrial district. ISIS itself took control of villages to the north of Aleppo, consolidating its control over northern Syria. However, continued infighting allowed government forces to reorganize, break a blockade of part of the city, and further consolidate their positions. Meanwhile, the situation of the population in Aleppo continued to deteriorate: by this point, over one million people had already left the fifty neighborhoods located in the eastern, opposition-held areas, mostly to escape barrel bombing and shelling, while these neighborhoods also hosted around 512,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs). Then on 8 May 2014, a massive explosion destroyed the Carlton Hotel near the citadel: the opposition had built a seventy-five-meter-long tunnel underneath it, fitted with explosives, a new tactic repeatedly used afterward against government bases in the Old City and citadel, with massively destructive effects.15

By 2015 the conflict had become a war of attrition, and, toward the end of the year, Russia increased its military support of the Syrian government and prepared to intervene directly. In October, government forces also launched a new offensive near the city to regain control of the international highway to the south and toward Kuweires military air base to the east, which had been under siege for two years by ISIS. Both operations were successful, with Russian air support and the presence of Iranian militias proving decisive. They also accelerated the displacement of the city’s population, with the evacuation of entire districts.16

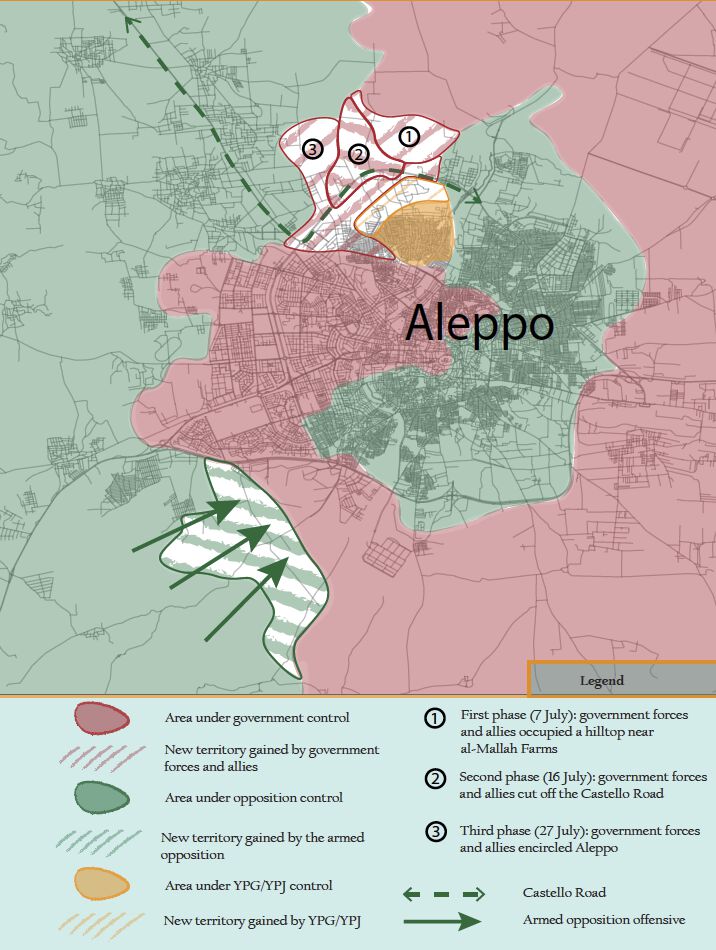

These developments led to the retaking of Aleppo by the government in 2016. At the beginning of the year, a cease-fire brokered by Russia and the United States had briefly allowed life in Aleppo to take a normal turn, but the support provided by Russia, Hezbollah, and the Iranian government continued to change the military balance on the ground. Despite setbacks, by July the government had completed its encirclement of the city, cutting off the corridor linking the areas controlled by the opposition to the Turkish border. Nevertheless, the siege of the city was broken within days by an opposition counterattack on the Ramousah district, opening a way into eastern Aleppo and leading to a response by the Syrian army supported by the Russian air force. Meanwhile, opposition groups and a powerful international force started a campaign to eliminate ISIS from the region. This helped government forces consolidate control of northern parts of the city and again place Aleppo under siege (fig. 10.3).

Figure 10.3

Figure 10.3After heavy bombing hit the eastern part of the city controlled by the opposition, pressure from government and allied forces gradually forced the opposition to accept a cease-fire, permitting aid delivery.17 With the mediation of Turkey and Russia, an agreement was reached to evacuate over thirty-five thousand opposition fighters, as well as part of the civilian population, and transfer them to Idlib Province, an operation carried out between 15 and 22 December 2016, effectively ending the siege and the war in Aleppo.

The Impact of the War on the Population

The population of Aleppo was estimated at around 3,078,000 on the eve of the war, in 2010. It had fallen to less than a million by 2015 at the peak of the fighting.18 Although it is difficult to know precisely the number of direct casualties from the war in the city, estimates suggest that 25,000–30,000 civilians lost their lives, with a further 10,000–15,000 casualties among combatants.19 Throughout the conflict, Aleppo was divided in two, the western side controlled by the government and the eastern side by the opposition. Although the entire city was involved in the conflict and suffered bombing and destruction throughout, most of the fighting took place in the center, the area surrounding the ancient Aleppo Citadel, and on the east side.

The population stranded in the city endured severe hardship, with frequent cuts to the supply of water,20 electricity, and food,21 and constant exposure to shelling and bombing. Access to healthcare and basic necessities was severely impeded, and transit between different parts of the city was almost impossible, as well as extremely risky. Hundreds of people were killed by sniper fire at the crossing between areas held by the government and the opposition, and it became increasingly difficult to transport goods through this zone. Relief provided by humanitarian organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent was occasionally granted access by the different factions, and food rations were delivered in both opposition- and government-held areas, although this help was always limited and insufficient.22

It is estimated that one-third of the school buildings in Aleppo were either damaged or used for other purposes during the conflict, such as shelter for displaced persons. Frequent bombing and casualties among teachers and children forced many schools to close or drastically reduce activities. At one point, only 6 percent of children were attending classes, a situation that prompted the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to declare Syria’s children a “lost generation.”23

Various aspects of the city’s medical services were severely impacted. The city’s blood bank was bombed in 2012, leaving the city without blood supplies.24 By late 2014 all the major hospitals in Aleppo had suffered damage and were forced to cut services, leaving only forty doctors left in Aleppo to serve the needs of over a million people, compared to two thousand doctors before the war. Indeed, the World Health Organization (WHO) ranked Syria as the most dangerous place in the world for health workers.25 The lack of vaccinations favored the resurgence of infectious diseases, while poor hygienic conditions favored a recurrence of cholera, and the destruction of pharmaceutical plants resulted in a critical shortage of medicines and supplies for a variety of diseases, ranging from diabetes to epilepsy, hypertension, asthma, and cancer.26 As a result of all this, life expectancy in Syria dropped by twenty years, to fifty-five.

By mid-2016, most of the population of eastern Aleppo had fled, but an estimated 250,000 people still remained under siege.27 Aerial bombing became particularly intense in the last phase of the war, leading to a dramatic worsening of the condition of the civilian population.28

The Impact of the War on Urban Infrastructure and Cultural Heritage

Five years of conflict left Aleppo in rubble. The fighting and bombing campaigns at different stages of the war, with a huge spike in 2016, severely affected housing, commercial and industrial buildings, public services, infrastructure, and the city’s monuments and historical districts.

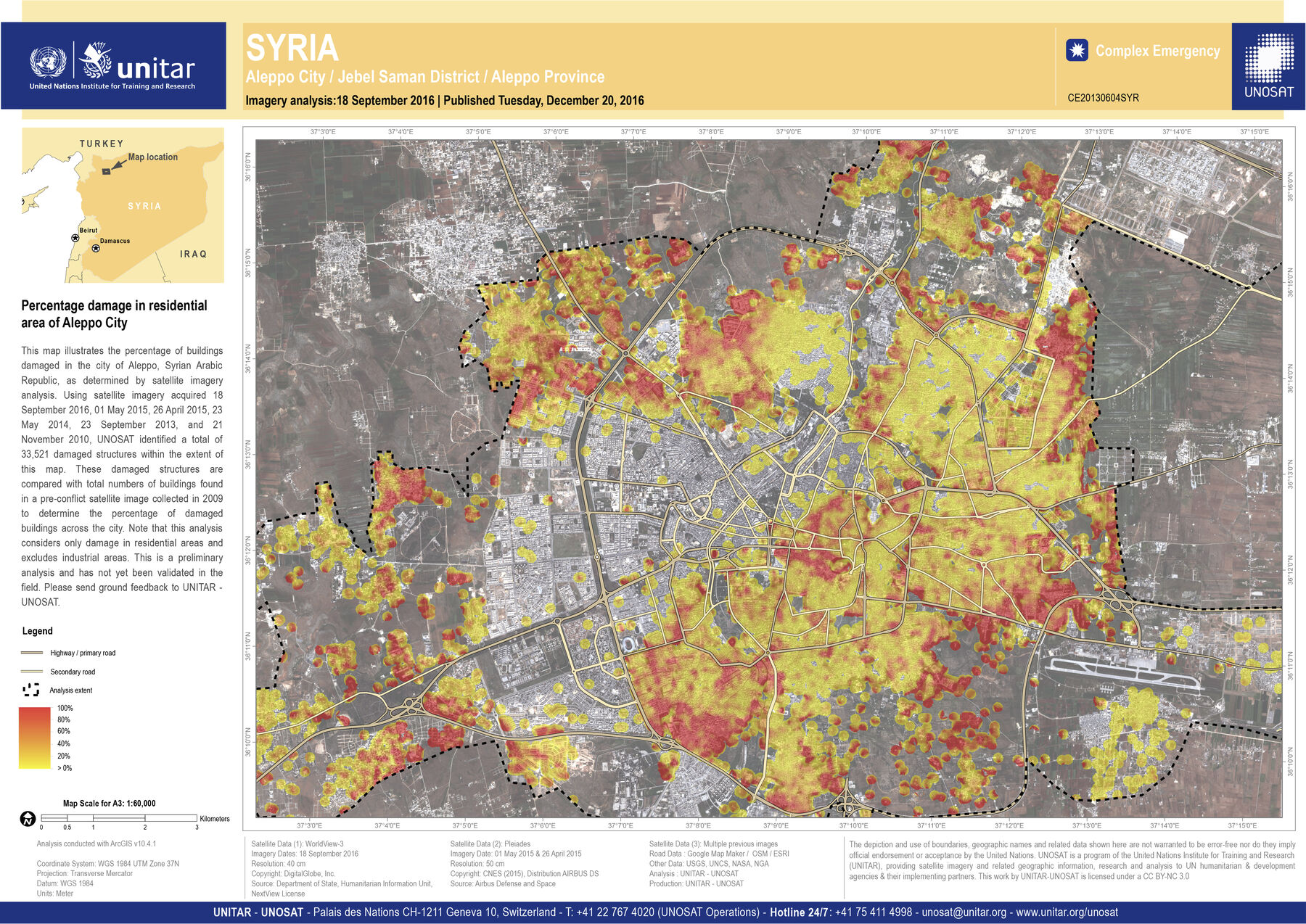

Assessment of physical damage was carried out during and after the war by the World Bank for the entire urban infrastructure, by UN-Habitat in 2014 and by the UN Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) in 2016 for the building stock, and by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), UNITAR, and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC) in 2017 for the monumental areas of the city.29

Aleppo’s thermal power plant, the largest in the country and the main source of electricity for 60 percent of the population, remained in the hands of the opposition until being recaptured by government forces in February 2016, resulting in significant damage and gradually putting it out of commission. As a consequence, from that point on, eastern and southern Aleppo received no power from the public network, while the western part of the city had only two to three hours of service per day. In the latter area, traditionally more affluent, private generators, solar panels, and makeshift wind-powered turbines partially compensated for the lack of power distribution, but at an increasingly high cost. The water distribution infrastructure was also badly damaged, with major interruptions due to shortages of fuel and electricity, although limited repairs were possible during the war, reestablishing some service to the city. Households often had to rely on wells or water trucks, with increasing health-related risks. The sewage treatment plant was not damaged, but suffered stoppages for lack of power. An initial estimate by the World Bank of damage to the city’s infrastructure indicates that it quadrupled from 2014 to 2016, to almost $8 billion.30

Arguably the most significant damage was to residential buildings. The city had 720,000 housing units in 2011, mostly in multistory buildings, largely in private ownership. About 50 percent of the units were abandoned during the war, due to damage, lack of basic services, and security. The greatest destruction occurred in the more densely populated and poorer eastern districts, where most of the aerial attacks were concentrated. Here, most of the housing is of an “informal” nature, built in areas of uncertain land tenure. Most of the commercial buildings in these districts were also damaged and over 70 percent of industrial structures damaged or destroyed. A 2018 report by UNITAR and UNESCO documented damage at the end of 2016 to more than 33,500 structures in Aleppo.31 The intensity of structural damage varied from a maximum of 65 percent in the central al-Aqabeh neighborhood to 50 percent in the periphery.32 Figure 10.4 shows a map of the intensity of damage in different parts of the city in September 2016, before the final fight for control, characterized by massive aerial bombing.

Figure 10.4

Figure 10.4The areas surrounding the citadel suffered heavy damage due to shelling, aerial bombing, and tunnel bombs placed beneath buildings.33 The more significant losses resulting from the conflict are concentrated to the southeast of the citadel, and include, among other structures, the Madrasa al‐Sultaniyya (built in 1223), the al-Khusrawiyya complex (1531–34) designed by Mimar Sinan, the al-Adiliyya Mosque (1553), and the al‐Utrush Mosque (1398). Some of the most important historical caravanserais, or inns, the khans, were also severely damaged, including the Khan al-Sabun of the Mamluk period (late fifteenth century), and the Ottoman-era Khan al-Nahhasin (1556). Like the Carlton Hotel, another important building dating from modern times, the New Saray government palace was completely destroyed by tunnel bombs (fig. 10.5). The celebrated Aleppo Citadel was also damaged, as its walls and towers along the north and east sides were hit by shelling. An internal tower and some of the buildings were also destroyed, although damage was relatively limited inside the complex.

The most significant heritage losses involved the Great Umayyad Mosque, including the destruction of its eleventh-century minaret in 2013 (fig. 10.6) and cracks in the structure of the building. Many precious historical manuscripts were also looted; the historical wooden minbar, or pulpit, was dismantled and stolen; and many wooden doors and decorations were burned. Furthermore, many sections of the al-Madina Souk area and other medieval buildings in the city were destroyed, severely damaged, or burned as a result of fighting.34

Figure 10.6

Figure 10.6After the end of the conflict in December 2016, the situation in Aleppo rapidly improved, although the city is far from regaining the position of being the economic powerhouse that Syria enjoyed before the war.35 Many people have returned and life has restarted, and some important restoration projects have been implemented with local and national resources, and with the help of some international agencies, such as UNDP, UN-Habitat, and AKTC.36 However, economic reconstruction and development have proven slower than expected and hoped, largely due to the international sanctions against the Syrian government, which have prevented foreign investment and the transfer of resources to the country.37

Conclusion: Lessons for the Protection of Culture in Armed Conflict

The effectiveness of the international system of protection for populations and cultural heritage during conflict is put into question by the immense suffering the civil war imposed on the population of Aleppo and the massive damage suffered by a World Heritage City of such importance, not to mention the damage suffered by other historical cities such as Homs and Bosra and archaeological sites of global significance, including Palmyra, Apamea, Mari, and Ebla. Yet the United Nations system did, in the post–World War II period, develop tools to address situations of this nature.38 For cultural heritage protection, the main tools are the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, the 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, and the 1972 Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage.

The 1954 Hague Convention introduced very specific obligations for its signatories, to prevent and limit damage to movable or immovable cultural heritage (including “groups of buildings which, as a whole, are of historical or artistic interest”) and more generally to buildings dedicated to cultural activities (museums, libraries, archives, etc.). The convention applies also to “conflicts not of an international character.” Syria is a signatory to the convention (although not of its First and Second Protocols), as are all the other states directly or indirectly involved in the conflict. It obliges state parties to respect cultural heritage by avoiding its use for military purposes (Article 4.1) and by preventing acts of theft and pillage of cultural properties (Article 4.3). Nonstate actors are also bound to apply its provisions (Article 19.1). Even sanctions are foreseen in case of breach of the convention (Article 28). However, at no time during the conflict in Syria, and in particular in Aleppo, has the Hague Convention been implemented, respected, or applied by the actors involved. While the 1970 convention has been implemented to intercept looted Syrian antiquities, observers agree that its impact on the illicit trade has been very limited. The 1972 convention has no provision for situations of conflict, but it calls for international cooperation for the preservation of World Heritage Sites. All states involved in the conflict are signatories of the 1972 convention and were therefore obliged to limit the damage they caused to Aleppo.

The UN Security Council has acted to protect Syrian cultural heritage by adopting two resolutions, 2199 of February 2015 and 2347 of March 2017, the latter of which “condemn[ed] the unlawful destruction of cultural heritage, inter alia, destruction of religious sites and artefacts, as well as the looting and smuggling of cultural property from archaeological sites, museums, libraries, archives, and other sites . . . notably by terrorist groups” (para. 1).

In spite of these and other important appeals, no effective response mechanism to limit the destruction of cultural heritage was put in place during the conflict. In 2013, UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee inscribed all six Syrian World Heritage Sites (Damascus, Aleppo, Palmyra, the Crac des Chevaliers, the Ancient Villages of Northern Syria, and Bosra) on the World Heritage in Danger List, but, again, little concrete help was provided. In fact, most Western countries applied sanctions to Syria that prevented the transfer of money and technical assistance, even for cultural heritage protection, a situation that changed only in 2021. During the conflict, the only help came from the European Commission, a European Union body, which financed a multiyear project, implemented by UNESCO and by the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM), to provide support for the conservation of Syrian sites, although most of the activities were carried on outside the country.39 However, this project was not extended after its completion in 2020.40

Similar observations could be made in relation to the implementation of humanitarian laws in the event of armed conflict, in particular the fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, which has been ratified by all states in the conflict (in fact by all states worldwide). It is clear that these treaties have revealed major shortfalls in providing protection to the population and to cultural heritage during a conflict of a non-international nature, such as the Battle of Aleppo.

UNESCO has worked in the past few years to address the weakness of the present system of international heritage protection by launching important initiatives.41 It is clear, however, that awareness-raising is not sufficient: to increase heritage protection during conflict, existing mechanisms need to be substantially reinforced through a more systematic integration of cultural protection into humanitarian interventions and a greater involvement of military forces. Recent examples of successful operations (such as that of the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali [MINUSMA], created in 2013) show that it is possible to embed cultural heritage protection into military operations. Indeed, Security Council resolution 2347 linked the protection of cultural heritage to the maintenance of peace and security, suggesting that peacekeeping operations could be mandated to carry out such tasks. In 2018, the European Union Common Security and Defence Policy endorsed the “protection of cultural heritage” as a line of operation for missions.

This approach should at a minimum be extended to all UN peacekeeping missions where sites of cultural significance are located, while the current trend seems to go in the opposite direction. A more active role for humanitarian organizations, such as the Red Cross, should also be promoted, and financial support provided to expand their role for cultural heritage protection during protracted conflicts. Short of this, during conflict, the protection of cultural heritage, an essential constituent of social identity and cohesion, will remain in the realm of goodwill declarations.

Biography

- Francesco BandarinFrancesco Bandarin is an architect and urban planner. From 2000 to 2018 he was the director of the World Heritage Centre and Assistant Director-General for Culture at UNESCO. He is currently special advisor of the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM), senior advisor of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, a member of the Advisory Board of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, and a founding member of the international nongovernmental organization OurWorldHeritage. His recent publications include The Historic Urban Landscape (2012), Reconnecting the City (2015), and Re-shaping Urban Conservation (2019).

Suggested Readings

- Leila Amineddoleh, “The Legal Tools Used before and during Conflict to Avoid Destruction of Cultural Heritage,” Future Anterior 14, no. 1 (2017): 37–48.

- Francesco Bandarin, “The Reconstruction and Recovery of Syrian Cultural Heritage: The Case of the Old City of Aleppo,” in Collapse and Rebirth of Cultural Heritage, ed. Lorenzo Kamel (New York: Peter Lang, 2020), 45–77.

- Ross Burns, Aleppo: A History (New York: Routledge, 2017).

- Raymond Hinnebusch and Adham Saouli, The War for Syria (New York: Routledge, 2020).

- UNESCO and UNITAR, Five Years of Conflict: The State of Cultural Heritage in the Ancient City of Aleppo (Paris: UNESCO, 2018).

- Carmit Valensi and Itamar Rabinovich, Syrian Requiem: The Civil War and Its Aftermath (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021).

Notes

Samer Abboud, Syria (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016); Ross Burns, Aleppo: A History (New York: Routledge, 2017); and Raymond Hinnebusch and Adham Saouli, The War for Syria (New York: Routledge, 2020). ↩︎

Syrian Center for Policy Research (SCPR), The Conflict Impact on Social Capital: Social Degradation in Syria (Damascus: SCPR and Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, 2017). ↩︎

Aron Lund, The Factory: A Glimpse into Syria’s War Economy (New York: Century Foundation, 2018). ↩︎

UNDP, Human Development Report 2016 (New York: UNDP, 2016). ↩︎

SCPR, Forced Dispersion: A Demographic Report on Human Status in Syria (Damascus: SCPR, 2016). ↩︎

UNHCR, “Syria: Operational Update,” January 2020. ↩︎

Cheikmous Ali, “Syrian Heritage under Threat,” Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 1, no. 4 (2013): 351–66. ↩︎

Helga Turku, The Destruction of Cultural Property as a Weapon of War: ISIS in Syria and Iraq (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). ↩︎

Susan Schulman, “From Homs to Aleppo: A Journey through the Destruction of the Syrian War,” RUSI Journal 163, no. 1 (2018): 62–81. ↩︎

Research funded by the American Schools of Oriental Research analyzed 3,641 sites in Syria, comparing pre-2011 imagery with site surveys during the conflict. Of the sites surveyed up to 2017, pre-2011 imagery revealed illegal digging at 450, with an additional 355 added in the post-2011 era. Ninety-nine of the sites already marked by looting pits before 2011 were active again after this; the rest were the work of looters exploring previously undisturbed sites. See Jesse Casana and Elise Jakoby Laugier, “Satellite Imagery‐Based Monitoring of Archaeological Site Damage in the Syrian Civil War,” PLoS ONE 12, no. 11 (2017), https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0188589. ↩︎

There have been several groups monitoring the Syrian conflict, supported by international organizations (see reports by UNDP, UNICEF, UNHCR, UN-Habitat, UNESCO, UNITAR, and the World Bank), governments (including reports by the United States Agency for International Development or USAID, the US Congress, the Atlantic Council, and the International Institute for Environment and Development), and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and research organizations (e.g., Caerus Associates, the Shattuck Center, the Syrian Center for Policy Research), to mention but a few. ↩︎

Keith A. Grant and Bernd Kaussler, “The Battle of Aleppo: External Patrons and the Victimization of Civilians in Civil War,” Small Wars & Insurgencies 31, no. 1 (2020): 1–33; Armenak Tokmajyan, Aleppo Conflict Timeline (Budapest: Central European University, 2016); David Kilcullen, Nate Rosenblatt, and Jwanah Qudsi, Mapping the Conflict in Aleppo, Syria (Washington, DC: Caerus Associates, 2014); and Reuters, “Timeline: The Battle for Aleppo,” 14 December 2016. ↩︎

The opposition groups were part of Liwa al-Tawhid, the largest of the two coalitions forming the Aleppo Military Council (AMC), which led the battle for the city. At some point, the AMC had between eight thousand and ten thousand fighters, and another ten thousand noncombat members. ↩︎

On 1 October 2014, UNESCO director-general Irina Bokova stated that, as a signatory to the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, Syria was obliged to safeguard its heritage from the ravages of war. See Oliver Holmes, “Fighting Spreads in Aleppo Old City, Syrian Gem,” Reuters, 1 October 2012. ↩︎

Martin Chulov, “Bomb under Hotel Signals New Focus of Syrian Oppositions, with Struggle for City Likely to Be Final Showdown,” Guardian, 8 May 2014. ↩︎

Tom Miles, “United Nations Says 120,000 Displaced in October,” Reuters, 26 October 2015. ↩︎

According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), Aleppo was hit by 4,045 barrel bombs in 2016, with 225 falling in December. ↩︎

After the end of hostilities in 2016, many people returned to the city, and the population has since then steadily increased, although it still remains at a much lower level than before the war. As of 2020, there are an estimated 1,916,000 people in Aleppo; it will likely take ten more years before the population returns to its 2010 level. ↩︎

These are the victims documented by the Violation Documentation Center in Syria (VDC), an NGO that attempts to document civil rights violations in the country. See VDC, “Monthly Statistical Report on Casualties in Syria: March 2020,” https://vdc-sy.net/monthly-statistical-report-casualties-syria-march-2020-en/. ↩︎

El-Dorar, “After the Water Cut Off for 80 Days, Aleppo Water Plants Starts [sic] Pumping,” 3 March 2016; and al-Arabiya, “Water Returns to Syria’s War-Torn Aleppo,” 4 March 2016. ↩︎

Tokmajyan, Aleppo Conflict Timeline. ↩︎

ICRC, “Syria: Aleppo Civilians under Attack,” news release 14/65, 22 April 2014; and “Life in a War-Torn City: Residents of Aleppo Tell Their Stories,” International Review of the Red Cross 98, no. 1 (2016): 15–20. ↩︎

UNICEF, Syria’s Children: A Lost Generation? Crisis in Syria: Two-Year Report 2011–2013 (New York: UNICEF, 2013). ↩︎

Nayanah Siva, “Healthcare Comes to Standstill in East Aleppo as Last Hospitals Are Destroyed,” British Medical Journal 355 (2016): 355. ↩︎

From March 2011 to June 2016, there were 382 attacks on medical facilities, and 757 medical personnel were killed, according to the NGO Physicians for Human Rights. The World Health Organization has repeatedly expressed its concern for the destruction of hospital facilities. See WHO, “WHO Condemns Massive Attacks on Five Hospitals in Syria,” public statement, 16 November 2016. ↩︎

Physicians for Human Rights, “Syria’s Medical Community under Assault,” October 2014. ↩︎

BBC, “Syria Conflict: ‘Exit Corridors’ to Open for Aleppo, Says Russia,” 28 July 2016. ↩︎

These are very uncertain figures, varying from over three hundred thousand down to around 130,000, according to different sources (e.g., the UN and the local council of Aleppo). Attempts to provide humanitarian help to the population besieged in eastern Aleppo failed on two occasions in 2016 (March and July) when UN convoys to the area were authorized to provide for a lower number of beneficiaries (sixty thousand), but in the end they were not delivered. See Annabelle Böttcher, “Humanitarian Aid and the Battle of Aleppo,” News Analysis, Center for Contemporary Middle East Studies, University of Southern Denmark, January 2017. ↩︎

UNESCO and UNITAR, Five Years of Conflict: The State of Cultural Heritage in the Ancient City of Aleppo (Paris: UNESCO, 2018); and AKTC, Old City of Aleppo: Building Information and Preliminary Damage Assessment in Three Pilot Conservation Areas (Geneva: AKTC, 2018). ↩︎

World Bank, Syria Damage Assessment of Selected Cities Aleppo, Hama, Idlib: Phase III, March 2017 (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2017). ↩︎

UNESCO and UNITAR, Five Years of Conflict. For a comprehensive analysis of damage to Syrian cities, see REACH and UNITAR, Syrian Cities Damage Atlas: Thematic Assessment of Satellite Identified Damage (Châtelaine, Switzerland: REACH, March 2019). See also UN-Habitat, City Profile, Aleppo: Multi Sector Assessment (Damascus: UN-Habitat, May 2014). ↩︎

Francesco Bandarin, “The Reconstruction and Recovery of Syrian Cultural Heritage: The Case of the Old City of Aleppo,” in Collapse and Rebirth of Cultural Heritage, ed. Lorenzo Kamel (New York: Peter Lang, 2020), 45–77. ↩︎

Maamoun Abdulkarim, “Challenges Facing Cultural Institutions in Times of Conflict: Syrian Cultural Heritage,” in Post-trauma Reconstruction, vol. 2, Proceedings Appendices, Colloquium at ICOMOS Headquarters, Charenton-le-Pont, France, 4 March 2016 (Paris: ICOMOS, 2016), 9–11; and Laura Kurgan, “Conflict Urbanism, Aleppo: Mapping Urban Damage,” Architectural Design 87, no. 1 (2017): 72–77. Several assessments have been carried out concerning damage to the historical areas of Aleppo. The UNESCO and UNITAR 2018 survey covers the area inscribed in the World Heritage List and is based on satellite data. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture 2018 assessment covers the three main historical areas and is based on drone and field analysis. ↩︎

Ross Burns, “Weaponizing Monuments,” International Review of the Red Cross 99, no. 906 (2017): 937–57; and Rim Lababidi, “The Old City of Aleppo: Situation Analysis,” e-Dialogos: Annual Digital Journal of Research in Conservation and Cultural Heritage 6 (June 2017): 8–19. ↩︎

Victor Gervais and Saskia van Genugten, eds., Stabilising the Contemporary Middle East and North Africa: Regional Actors and New Approaches (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020). ↩︎

Directorate General for Antiquities and Museums (DGAM), The Intervention Plan for Aleppo Ancient City (Damascus: DGAM, 2018); and DGAM, State Party Report on the State of Conservation of the Syrian Cultural Heritage Sites (Damascus: DGAM, 2019), report presented to the 42nd Session of the World Heritage Committee, Baku, Azerbaijan, 2018. ↩︎

As of early 2020, more than 11.1 million people in Syria were still in need of humanitarian assistance, 6.2 million were internally displaced, and an additional 5.6 million had registered with the UNHCR as refugees in nearby countries. See Council on Foreign Relations, “Global Conflict Tracker: Civil War in Syria,” 9 April 2021; and Carmit Valensi and Itamar Rabinovich, Syrian Requiem: The Civil War and Its Aftermath (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021). ↩︎

Leila Amineddoleh, “The Legal Tools Used before and during Conflict to Avoid Destruction of Cultural Heritage,” Future Anterior 14, no. 1 (2017): 37–48. ↩︎

Silvia Perini and Emma Cunliffe, Toward a Protection of Syrian Cultural Heritage (Girona, Spain: Heritage for Peace, 2014). ↩︎

Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture of the European Commission, “Emergency Safeguarding of the Syrian Cultural Heritage,” in Mapping of Cultural Heritage Actions in European Union Policies, Programmes and Activities (Brussels: European Commission, August 2017), 33. ↩︎

An important awareness-raising initiative, named #Unite4Heritage, was launched in 2015 by the director-general of UNESCO to promote the involvement of civil society in the protection of heritage and the fight against its deliberate destruction by violent extremist groups. That year, UNESCO’s General Conference—the biannual meeting of the organization’s member states—adopted the “Strategy for the Reinforcement of UNESCO’s Action for the Protection of Culture and the Promotion of Cultural Pluralism in the Event of Armed Conflict.” An emergency fund was established to support the strategy. ↩︎